An Interview with

Dr. Bob Shipp

Dr. Bob Shipp is widely recognized as one of the most authoritative voices in red snapper management in the nation. He’s spent some 18 years—six separate 3-year terms—as a member of the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council, including three terms as chairman. He’s also chairman emeritus of the Department of Marine Sciences at the University of South Alabama.

Here are some of his thoughts on how we got to where we are today in Gulf red snapper management, deemed by most anglers as unnecessarily repressive on recreational harvest, and on where we need to go to make things better.

BY Frank Sargeant

CA: How did we get to the current status of management?

DS:There was a time when red snapper was overfished and undergoing overfishing—too many elements impacting the stocks, both adult and juvenile. This was in the late ‘80s. There were not a lot of harvest rules on either commercial or recreational anglers—anglers back then had a seven-fish bag limit and no size limit. Maybe more importantly, there was a huge wild shrimp trawl fishery at the time. Studies showed that the trawls in some areas were killing over 80% of the juvenile red snapper, so the whole system was disrupted. There was no question that the numbers were way down, particularly in the larger fish, and something had to be done to preserve the fishery. Today’s rules are the result of an effort to turn that around, which we have done, but in my opinion we’ve now gone too far the other way, to the point where we’re not getting maximum sustainable harvest out of this fishery or giving fishermen what they could be enjoying without harm to it.

CA: What factors have brought fish numbers back?

DS: First, the trawl fishery for shrimp is just a fraction of what it once was. The combination of cheap, farm-raised shrimp, high fuel prices in the ‘90s and the requirement for use of fish excluder devices to allow escapement of juvenile fish all made shrimping far less profitable than it was once, and a lot of boats just quit operating. So the destruction of the juveniles is no longer a significant problem from these trawls.

Secondly, I think the cumulative numbers of artificial reef structures placed in the Gulf over the last 25 years are having a huge impact on red snapper, which requires reef habitat for success. There are literally thousands of reefs out there today, both put down by fishermen and by government agencies, everything from washing machines to 300-ft.-long ships and discarded oil rigs; and the Corps of Engineers now actually encourages anglers to put them down in a 1,200-sq.-mile area of the northern Gulf, so we’ve had a big change in the available habitat there, from a soft mud or bare sand bottom to all these structures that form the base of the food chain. Some researchers argued early on that the reefs were simply concentrating the fish that were already there, but that’s been proven to not be the case—the reefs are a huge population multiplier.

And, of course, the very tight harvest rules have also greatly increased the snapper population. The take today is a fraction of what it was at one time, and all the factors together in recent years have resulted in a larger average size of the fish, so that the take, which is limited by poundage, has gone down in numbers of fish.

CA: How good are the stocks today, in your opinion?

DS: I think there are more and larger red snapper on average in the Gulf of Mexico today than there have been in modern history. Not only are the traditional areas off North Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas completely loaded with fish, to the point that reef anglers can’t get baits down for grouper and other reef species, but the larval distribution has restored a very good fishery off central Florida, where there had not been fishable populations for generations. Adult snapper don’t migrate, so the fish that settle on a reef will remain in that general area throughout their lives so long as the habitat doesn’t get covered with sand, and they’re long-lived fish—we think they might average 20 years or so in the wild, with a few living to be 40 or more. A lot of the fish that are on the reefs today will be there for a long time, in other words, with the protective rules we have in place.

CA: Does this mean we can expect a lot of monster red snapper on the reefs in the future?

DS: Not necessarily monsters, but probably a lot of big fish. Snappers get most of their growth in their first 10 years—a 20-pounder might be 10 years old, or it might be 25—they don’t keep on getting bigger indefinitely. Commercial fishermen actually prefer two to four pounders because they bring the best price on the market, but anglers all sort of feel management for bigger is better, we know.

CA: How has the management of these stocks, now apparently so healthy, gone off track, in your opinion?

NS: It’s definitely mostly a problem of the accuracy of the population estimates. If we use flawed data that indicates we are harvesting too many fish for the population to maintain itself at the desired level, then by law, the federal regulators have to put tighter restrictions on the fishery. I think that’s what we have today. For example, in 2014, NOAA Fisheries estimated about 1.5 million pounds of red snapper were harvested off Alabama. At the same time, the state of Alabama, with an extensive survey system that’s generally recognized as far more accurate, found that only about 500,000 pounds had been taken—one-third as much.

There’s actually good momentum right now to improve this system. I just returned from a meeting in New Orleans with 50 fishery scientists where the primary topic was how we can generate “fishery independent data,” or information that comes from outside the catches of both recreational and commercial fishing reports to give us a better overall picture of the actual red snapper populations. Alabama Senator Richard Shelby helped to get a $10 million appropriation into the federal budget for this effort, and it looks like it should come into being soon—in the future, hopefully we’ll set limits based on current and accurate population information.

CA: If you were made the Gulf red snapper czar today, what would you do to make things right?

NS: I like the IFQ commercial rules the way they are—the fishermen can take their quota whenever it’s best for them, there’s no derby causing fishing in unsafe weather, and there’s no glut on the market. The only thing I would change there is to eliminate the right of fishermen to lease out their shares—they’d have to fish it themselves or lose it.

For recreational anglers, I think we could go back to something like in the early 2000s, when we had 180 days open and a four-fish bag limit—the stocks were still going up under those rules, and there are a lot more fish, as well as more habitat today, so that should work and still preserve the fishery at a really high level. We may not see regulations that liberal for a while, but I’m hopeful we are definitely beginning to head in the right direction.

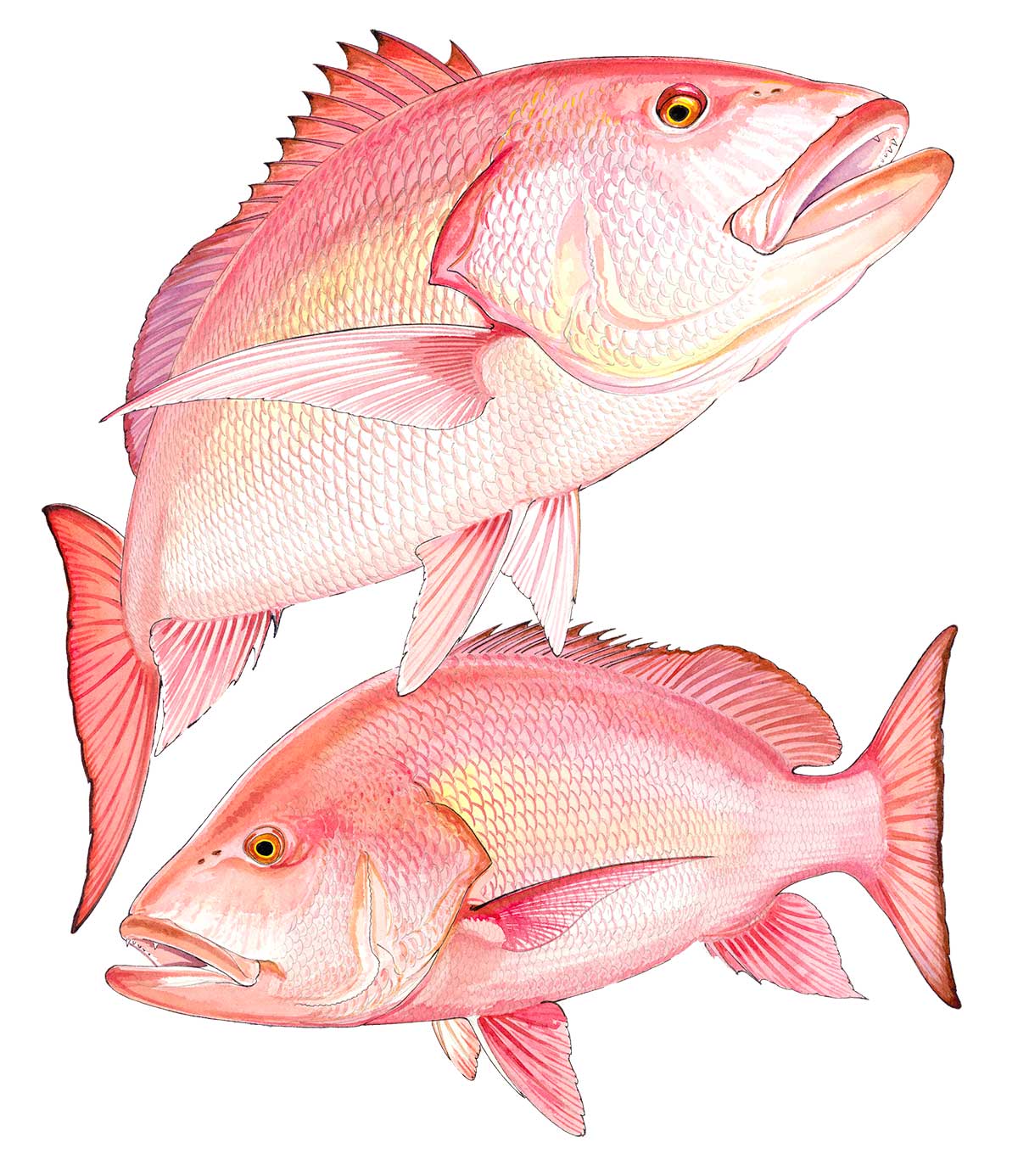

Dr. Bob Shipp’s iconic Guide to the Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico is a book that belongs on every saltwater angler’s bookshelf. The volume includes color illustrations and photos of hundreds of Gulf species, as well as a description of their life cycle and habitat preferences. It’s $26.95, signed by the author, from www.BobShipp.com.