BY NICK HONACHEFSKY

Image: Offshore fishing and rig fishing are nearly synonymous in Louisiana waters, and the state is still aggressively working with the oil and gas industry to keep existing structures in place as fishing reefs.

The state incentivized oil and gas companies in a cost benefit way to decommission their rigs. Essentially, the state has made it cheaper for the companies to remove, clean and float a decommissioned rig to a planning area where it then becomes reef habitat. These planning areas are agreed upon zones where rig material can be sunk for reef material, and are a positive example of how Louisiana’s reef program got the usually frictional recreational and commercial fishing industries to work together.

There were sit down meetings with members of both communities to hash out the best plan possible. The planning areas do not intrude on shrimp trawling grounds, and

are favorable spots where recreational anglers prefer to fish – known to anglers as a win-win “fish-uation”.

Underwater, the interlacing legs of an oil or gas rig (inset) become a platform for life, supporting an entire food chain, from colorful encrusting sponges to baitfish to the predators anglers love to target, including dolphin, tuna, snapper, grouper and more.

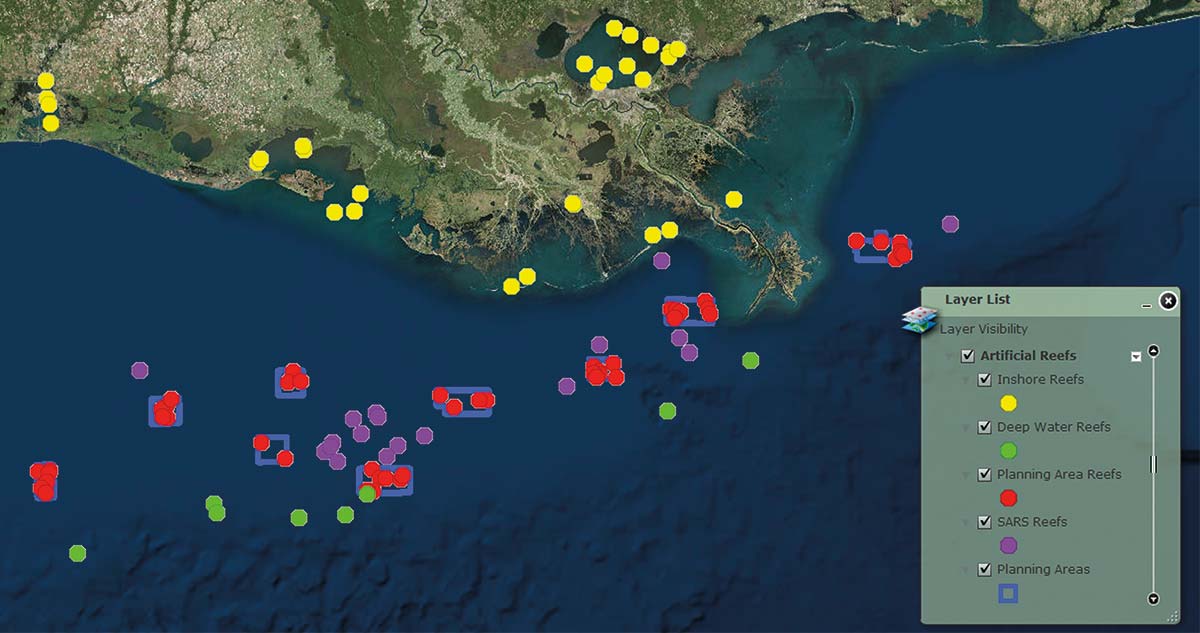

Indeed, the Rigs to Reef initiative is the highlight of the Bayou State’s reef concept and their success has served as a model for others, but their reef building program incorporates four distinct zones in both state and federal waters.

They are inshore, nearshore, offshore and deepwater. The inshore zone consists of 30 manmade reefs within Louisiana’s Coastal Basin, between the Louisiana Intracoastal Waterway and the Louisiana coastline, including Lake Pontchartrain. Reefs in this zone are made from varied low-lying material, including limestone and recycled crushed concrete. Prefabricated material such as reef balls create a piscatorial paradise for anglers searching out sheepshead, redfish, speckled trout, black drum and flounder. The Nearshore zone, consisting of five reef sites at Sulfur Mine, the Pickets, South Timbalier 86, Rabbit Island Pass, and the Nickel Reefs exist between the coastline of Louisiana and the 100-ft. depth contour, where a majority of oil platforms exist. These reefs also include rock piles and additional materials, including limestone and recycled concrete.

A large influx of funds from the BP oil spill settlement, allowed the state to build reef systems that are accessible to small boat anglers who can’t make the long distance runs offshore. Currently, the Sulfur Mine stands as the world’s largest artificial reef, comprised of 30 structures including platform material and 1.5 miles of old bridgework, while the Pickets contains 13,000 tons of limestone rubble and is designed to conserve and enhance the natural undulations on the seafloor. Those accessible reef systems will give anglers the ability to target both a mix of inshore and offshore species such as king mackerel, gray snapper, redfish and even seatrout.

Offshore, of course, are the planning areas for oil rigs and these are predominantly in the 30- to 70-mile range where 66 offshore reefs contain over 350 structures. Those are the hot spots to target more pelagic fish like yellowfin tuna, cobra and even marlin. And, as a result of the oil and gas industry moving even further out to prospect for fuels, Louisiana’s reef program is also expanding into deep water over 400 feet. The longer distance from land results in higher decommissioning costs, thus more incentive for companies to reef the materials. Currently, there are eight deepwater reefs, some of which are composed of multiple structures including Eugene Island 384, Garden Banks 236, Green Canyon 6, Mississippi Canyon 486, South Marsh Island 205, South Pass 89, Vermillion 395 and Vermillion 412.

Lousiana’s reef program covers both inshore and offshore waters and anglers can find reef locations by visting www.fishla.org.

A beautiful orange cup coral reef.

Reefing a rig is also a good preventative method against hurricanes which can beat up or even destroy oil platforms. So, rather than having the costs of disassembling and removing the rigs, the oil and gas companies join the program, cut the footings off the rig and float them into the planning areas where they are then sunk and laid on their sides so as to avoid being navigational hazards.

Perhaps what sets Louisiana’s reef program apart from other states has been the ability to get everybody working together, from oil and gas companies to fishery managers to recreational and commercial anglers. The results have been good for all sides, and more importantly, a boon for the fishery itself.

For anglers, there are more good things to come, no matter how deep they like to fish.